The values conversation is the second of three critical conversations for supervisors to have with team members and prospective hires. At ITX, we are implementing these conversations across the board, with all of our team members, in order to align them with our company’s goals, and to keep them aligned.

The commitment conversation gets us clear about each team member’s level of commitment to the company. One of the things we ask is for our team members to be committed to our values. This second conversation provides a more solid understanding of exactly what that means.

Why We Need the Values Conversation

With the commitment conversation, we got clear about what we expected from team members and what they could expect from us. This pact underway, we are ready to enter the next phase of building our relationship. The essence of this conversation is to provide an understanding of the organization’s values in order to produce alignment.

Whereas the commitment conversation is about clarity, the values conversation is about alignment.

The key benefits of the values conversation:

1. It creates an unchanging foundation for the organization’s culture that team members can rely upon, as well as a common view of who we are as a company.

2. It creates workability. Since each organization will have values that directly correspond to what makes it successful, aligning team members with those values increases productivity and efficacy. Overall behavior and decision-making are guided by consistent principles.

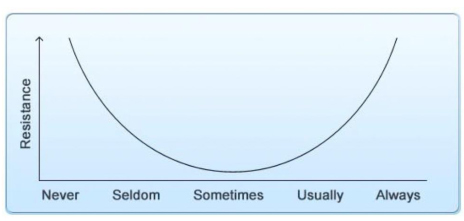

3. It is a clear measuring stick of alignment. Asking someone about his values tells us nothing. In most organizations, it is fairly easy for a team member to skate by with a very low level of adherence to the organization’s values. However, by implementing the values conversation, we can set a high bar and assess alignment.

4. It allows team members to live into, rather than subscribe to, values. Subscribing to values doesn’t produce alignment; living into them does. People can say they subscribe to a value, but that doesn’t compel them to do anything. It’s a much greater assertion to be able to say that we live into a value. In our organization, we expect a higher level of commitment, and we pass that onto our clients. We don’t try to sell ourselves by saying, “We’re ITX, and these are our values.” Instead, all of our team members embody those values and live into them.

What the Values Conversation Looks Like

Like the commitment conversation, this is a one-on-one discussion between the team member and the supervisor, and it needs to be an authentic conversation. The supervisor can’t just read from a piece of paper and say, “Oh, by the way, this is what you have to believe in, in order to work here.” These conversations are much more vital than that.

When supervisors first sit down with team members to have the values conversation, they explain its three key benefits as outlined in the previous section. It is important that supervisors convey the usefulness of the discussion before moving on. In fact, the effectiveness with which they do so will have great impact on the team members’ enthusiasm for the process and, ultimately, enrollment into the organization’s value system.

Next, supervisors get to the substance of the conversation: talking about the organization’s values. They break out the key words of the mission statement and define them as they apply to the organization. Four pieces of information are supplied for each word: its definition, its origin, why it’s important to the organization and, most important, the impact that value has on workability for the company.

For example, one of ITX’s values is integrity. If we ask someone to subscribe to integrity without explaining what it means to us, we’re begging for an empty promise to a vague idea. Sitting down with our team members and having a genuine discussion about it facilitates alignment in a way that would otherwise be impossible. People often use the word ‘integrity’ as a synonym for honesty, but our definition goes beyond that. At ITX, we believe that integrity is honoring our word by doing what we say we will do, and taking responsibility for cleaning up the mess when we don’t. Knowing that we make this distinction, a new team member will do infinitely better within, and for, our organization.

So, for ITX ’s value of integrity, our definition is that we honor our word and clean up the mess when we don’t. Its origin stemmed from our view that information technology has historically been a low- integrity business. Technical people tend to focus on technical things over relationships, and what we did was make relationships the most important part of ITX, even though we’re highly technical. For us, integrity has created great workability in all areas of the business.

Our other values are elegance, innovation, mastery, and success. Everyone’s definitions of those values is initially going to be different. If we don’t explain what we mean by those terms, they can’t produce alignment. Like the childhood game Operator, the variations distort the intended meaning if we don’t have the values conversation with everyone. How can we expect anything unique to be created if we force our team members to rely upon others’ definitions of elegant and innovative things? To be sure we are working toward a shared vision, we need to use inspired, but precise, language that aligns us to create our own definition. Then, once we ascertain that a team member’s definition of a value is in line with ours, we have to teach how to live it in our organization. We need to explain how to put the concept to use.

The supervisor must fold actual examples into the discussion that highlight how the implementation of those values benefits the organization as a whole. For instance, we might explain that a team member who is often on time often doesn’t waste other people’s time, and that puts the team member in integrity. If the team member is late once in a rare while, well, that happens, but to be in integrity at ITX, even then any mess that was caused has to be cleaned up immediately. It starts with a sincere apology. Then, if there was any kind of negative impact because of the delay, the team member must take responsibility for that mess.

The team member must be given time to ask questions. If this is a new hire, the team member’s queries and the supervisor’s attentive feedback will lay the groundwork for good communication, the cornerstone of a great relationship. Too often, we rush through team members’ first days of work, which is unfortunate, because that’s when we have the most impact on their outlook.

The conversation must be concluded by talking about the role of authenticity. It bears repeating that authenticity is crucial. The supervisor must tell the team member that it makes all the difference in the world in terms of how well someone is living into the values. If team members are being inauthentic about the values, then they are lying to themselves, the organization, and our clients. It’s very easy for someone to fall into this trap, because people don’t want to be seen as not following the values that they say they espouse. Ironically, the more authentic we can be about the times when we have been inauthentic, the more integrity we have. If we fess up when we make a mistake, we’ll earn others’ trust. It’s as simple as saying something like, “You know what? I was out of integrity. I said I was going to have it done, and I didn’t do it. What can I do to clean up the mess?”

When someone breaks an appointment with you, for example, don’t you get really annoyed if it’s accompanied by a big song and dance…every time? We not only stop believing that these people will ever be reliable about keeping their appointments, but then we start thinking of them as liars, as well. If a client thinks this about someone in your organization, do you think that client will believe you when you say the company espouses integrity? Authenticity means skipping the drama and being professional.

If we make a mistake or fail someone, we must not try to talk that individual into believing that we still have integrity, or that our failure was somehow justified; we have to show that we still have integrity by living into it, admitting our failure, and cleaning up the mess.

Values must be coupled with authenticity in order for us to be truly living into them.

Some Words of Caution

People cannot possibly be aligned with what we want if we simply toss pretty words at them without explaining what they mean to us. It doesn’t take long to make this abundantly clear and to leave no room for misinterpretation. But there are a few things of which we need to be aware. During this discussion, we must be mindful of distinguishing workability from judgment. It is crucial to convey that we are not using the values to judge. We have simply determined that these values work for us. At ITX, we believe that our value of integrity creates more workability. It’s not about whether integrity is good or bad; it’s just extremely useful in making our organization successful.

Putting the Values Conversation to Work

Now that we’ve gone over the system for implementing the values conversation, let’s wrap up the few remaining points so that it can be put to work immediately.

Since the hiring process has already exposed team members to our values, this conversation won’t be the first time that they are hearing about them. It will simply serve to deepen the alignment, since by this point, we will already be confident that the individuals are a fit for our values. If there are any huge surprises by the time we get to the values conversation, we need to look at our hiring process!

Also, if you haven’t yet thought about values as they relate to your organization, it is worth taking the time to thoughtfully consider which ones make it successful.

Values must be selected based on what creates the alignment that will make your organization successful.

Timing is everything. Have the values conversation as soon as you can after someone has committed to your company, during the first week of training, if possible. Instead of the supervisor walking a new hire around the office, making introductions, and talking at the team member as fast as possible, this authentic conversation will serve as a highly professional, inspiring entrée into the organization. Supervisors will probably find themselves in a longer conversation than they are used to with new team members because it will go so well. People get really excited when they see that the organization they just joined is all about values. It gives them a tremendous amount of personal satisfaction that they have been selected because they meet those values. They will also know that they will be supported in their new work environment, because every person there has also been chosen for the same reasons. What could make someone feel more like part of a great team?

We can employ the tool of the values conversation, or we can follow the lead of most companies and just give people a document that they’ll glance at and throw in a drawer. Then everyone can walk around telling each other stories about how they’re living the company’s values, using buzz words from the corporate literature in an effort to impress. Personally, if I want someone to commit to something I believe in, I know I have an infinitely better shot in a face-to-face discussion. There’s nothing like an authentic conversation to convey a vision, foster understanding, and bring about alignment.

The commitment and values conversations are an introduction to the company, giving team members an overview of how values work within the organization. This conversation will lead to the third discussion a company will want to have with its team members, the performance conversation.

© 2012 Ralph Dandrea. All rights reserved.